Jill Mueller

Jill Mueller is a London-based artist who was born in the United States, lived across the globe, and has settled in the UK. In our interview, which took place via email in the late summer of 2020, we talked about the ‘conceptual’ label, and whether or not it’s useful. We discussed the process of drawing on deeply personal experiences to inform work – specifically a BRCA1 gene mutation that replotted Mueller’s artistic course – and about writing as part of the artist’s toolbox.

Jill Mueller’s work is on display as part of Lockdown Residency until 30th November 2020. To visit the exhibition click here.

How did you become a Conceptual Artist?

It was in April (2020) during the Cel de Nord online residency that I first recognised what I do as conceptual. But the more I think about this question, the less sure I am of the answer. Not the how of it, but the truth of the self-appointed label – am I in fact a conceptual artist?

“In 2012 I tested positive for a hereditary genetic mutation called BRCA1. Women with this mutation have up to 87% chance of developing breast cancer...”

Fifteen years ago I came to art to become a figurative painter. I trained at a traditional atelier that focused on draftsmanship and painting skills and intended to build an art practice around that. Only later did I stumble my way into a broader practice that worked with more abstract concepts alongside aesthetics and figurative work. This was a slow process, but one that emerged from sudden and dramatic life changes.

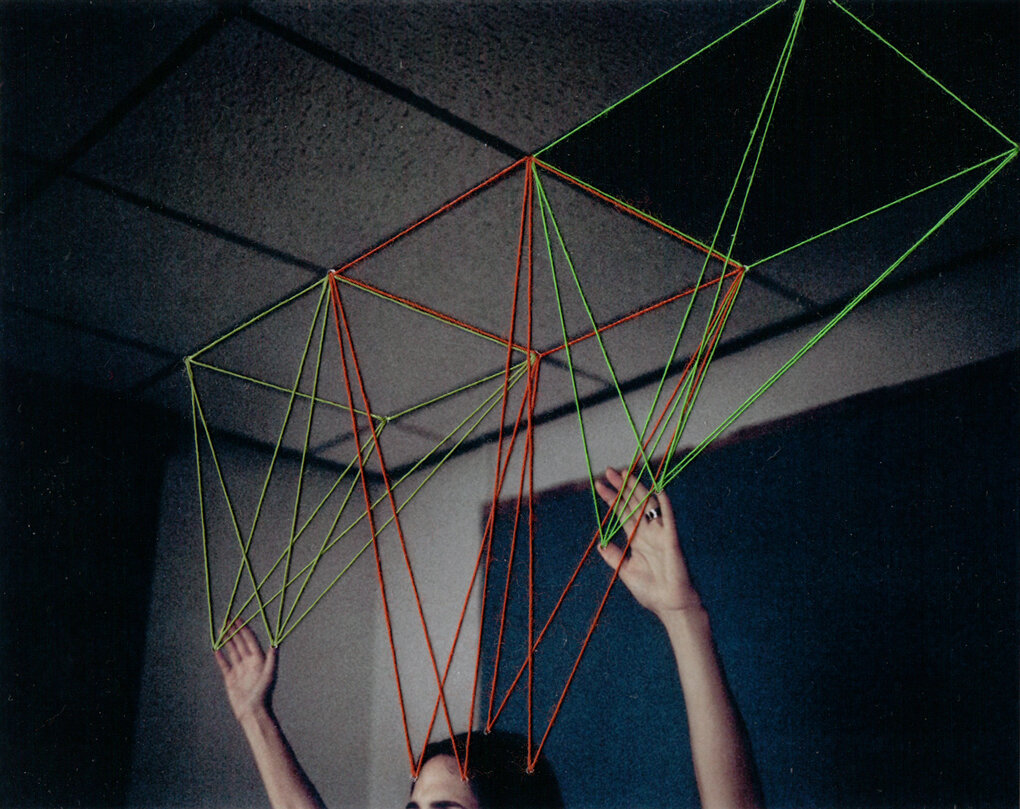

In 2012 I tested positive for a hereditary genetic mutation called BRCA1. Women with this mutation have up to 87% chance of developing breast cancer and up to 44% chance of developing ovarian cancer in their lifetime, and doctors recommend preventing those cancers by removing our healthy breasts and ovaries. From the day I received my results, I knew I wanted to engage my medical process creatively, but instinctively felt that I wouldn’t be able to paint my way through it. Instead I reached out to a photographer, Maja Daniels, to join me on what would become a multi-year collaboration to document and explore my medical journey through discussion, photography, creative writing and other artwork.

During this time, research and experimentation with new mediums and materials opened up my practice, and eventually I found my way to an MA in Art and Science at Central Saint Martins in London. What started as a creative detour now became a roadmap for my practice. I began to understand why I create – the importance of the process and ideas behind my work and the desire to create opportunities for viewers to encounter an artwork so that they can make their own meaning from it. Providing a safe space through artwork for thinking, self-reflection and to create empathy. Still, I didn’t relate the word conceptual to my work even then. Many people think of conceptual work as art that elevates ideas above aesthetics – often at the expense of artistic skill. This isn’t how I see my work – which is really a hybrid of layered concepts, story, aesthetics and skill. So many artists work in this way these days, especially at the intersection of art and science, without calling themselves conceptual artists. There is so much wrapped up in a word, and labels can be limiting. Perhaps I was mistaken in adopting one...

You mention your experience of becoming a medical patient – the surgical journey that came about as a result of discovering your BRCA gene mutation, and how you engaged with it creatively. In doing that, you became both the artist and the subject of that work.

Did having a double role in that medical process change the way it affected you emotionally?

Creating art while going through my medical experience provided opportunities for me to step outside the emotional immediacy of it all, to look at my medical process as if through the eyes of another person. At first, most of my emotional energy went toward being a patient, and I was so lucky to have another artist to help hold the creative energy for the project early on. As time passed, especially once I'd had my surgeries, Maja and I had to navigate our shifting roles as I became more empowered as an artist and less focused on being a patient. Although my physical healing happened fairly quickly, the emotional and mental adjustment took much longer. Making art provided a way for me to explore that complex process without feeling like I needed to hurry up and move on. It gave me space to dig into what I was feeling and why, and to think about how to express and share those experiences.

Maja and I rented a studio together for a month two years after my first breast surgery. During that time I began to respond to some of the images she’d taken of me in hospital, and I found my way to stitching into them. This creative physical interaction with my experience as a patient in those images – moments where I’d felt so vulnerable – provided another way into my emotional experience, and I began to reclaim my medical narrative and reshape it in a way that was really empowering.

Your own BRCA1 mutation is such deeply personal and emotionally rich subject matter. Was it difficult to move onto something else after something so deep? Where did you go next?

Because the BRCA project continues through talks and potential shows (and I’m working to get a book out into the world), I’ve not yet fully moved on from it. I’m keeping one foot in that work and I expect to for a long time to come. But my relationship to it has had to shift in order to be able to maintain that connection and still have reserves of energy to direct elsewhere. It has been difficult to navigate that process at times, but that comes with the deep territory!

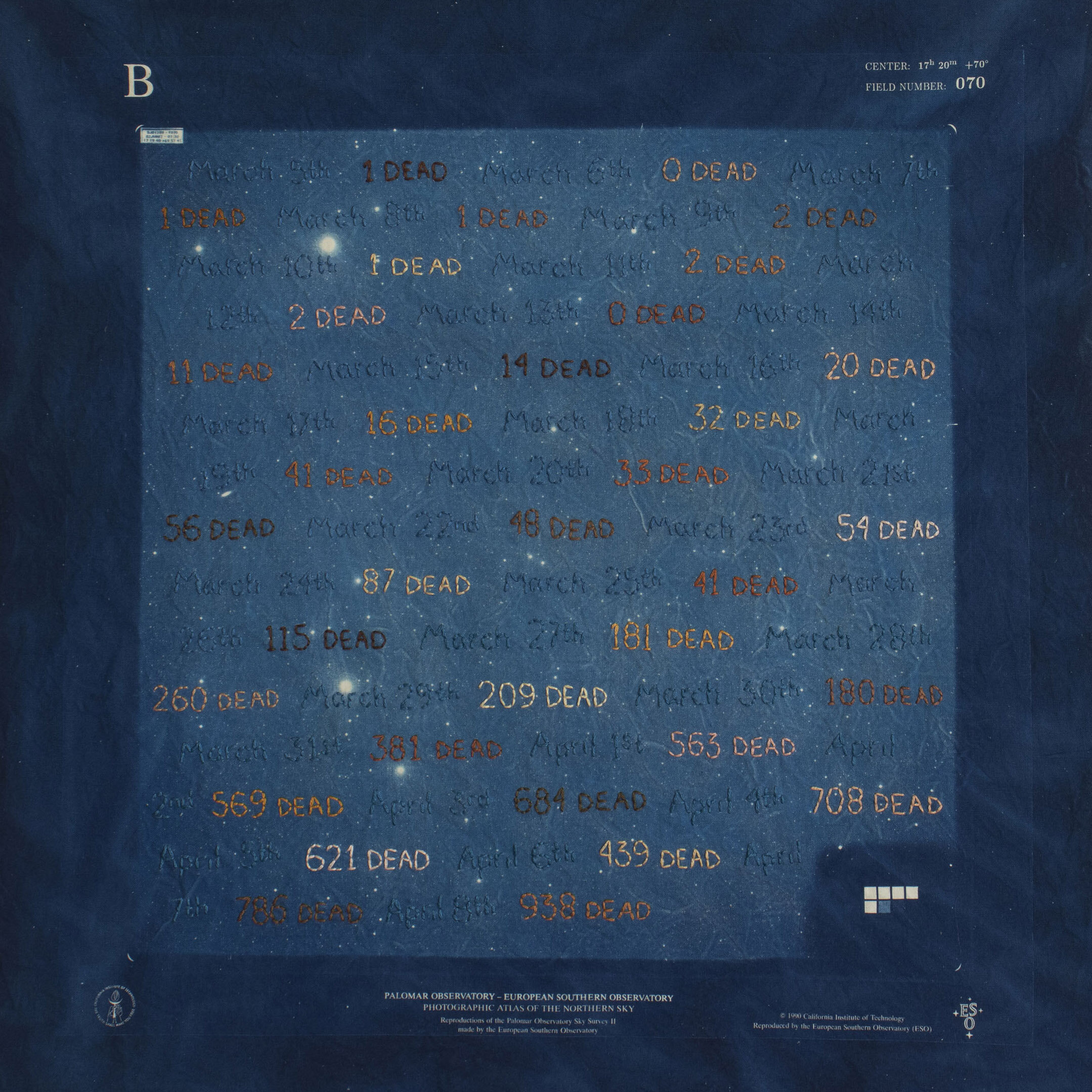

All of the work I do now stems from a deep personal connection to a subject or idea, and a few projects have emerged during lockdown. Over a few months, I made an embroidery project that documents the daily reported number of Covid-19 deaths in the UK. I wasn’t sure how to process the increasing number of deaths we were hearing about each day, but I surprised myself by wanting to engage that as an art project. It was less of a want than a need – I needed to use my hands to process the emotional distress I felt. I’ve used stitching in a few projects now, and the body’s memory of that physical activity, the almost ritualistic movements of the arm and hands, were very present for me. This project got me thinking and writing about ritual and its value for the big things in life, but also its importance in daily life. When I am out of sync with daily ritual, my focus and the work suffer. I might spend days circling around the work, making small adjustments or mistakes. It’s become clear that my creative mind and ritual are intertwined.

I remember hearing you talk about your family as a source of subject matter?

In late May I began a project documenting stories about my mom’s life through regular conversations over Zoom calls – she’s in Colorado and I’m in London. It’s been amazing to get to know her as a unique human being with her own life story. I’ve come to believe that none of us really know our parents – how could we without having travelled their paths? – but it’s been surprisingly insightful and emotional. And feels very collaborative, which I like. I’m not sure where the project is going, but for now I’m giving it the space and time it needs to grow into itself.

“ It’s a story about isolation and solitude, resilience and connection, and our human relationship with the remote wilds of nature. ”

I’m also just beginning to re-engage another project that’s been sitting on the back burner. Five years ago I rediscovered a short manuscript that my grandfather wrote in 1955 as part of the team that rescued an injured mountaineer on North America’s highest peak, Denali (then Mt. McKinley). The manuscript narrates an unbelievably treacherous five-day journey that set me off on a journey of my own as I compiled an archive of work – articles, photographs, artefacts, and interviews – about the mountain rescue and mountaineering at that time. It's a story about isolation and solitude, resilience and connection, and our human relationship with the remote wilds of nature. It’s such an exciting project, but one that needs the time and the right environment for me to engage with it authentically. I need to draw on my own experience as I engage the experience of those men in the wilderness, and I find it very difficult to do from a one-bedroom flat above a high street in London! I’m currently looking for a remote snowy residency to take it to.

I know that you're also a writer, and so it's not surprising to hear you talk about these projects like they are stories being told through your various methods of practice.

Do you see your writing as another art medium, or as a separate kind of creative output all of its own?

I used to see writing as something personal that I would use to document or interrogate things that were happening in my life, or for sharing an experience with people in my life. But over the past few years – especially working on See Me Through This (my BRCA project) – my relationship to writing and even the way that I write has changed. It has definitely become much more of an art medium that I can draw on to explore or creatively express an idea or story – and to prompt a viewer to think, to open them up to different experiences. I don’t generally write poetry, but perhaps my approach to writing within my art practice has become closest to that of a poet.

I’m increasingly interested now in stitching together or blurring the boundaries of writing and the visual in my work. Language is image as we read it – we often create visual equivalents or corollaries in our mind’s eye as we connect to the ideas conveyed by the words we’re taking in. I really love the idea that with just a few words or a text, we each create our own private images based on our thoughts and experiences. We all become creators in that moment.

See more of Jill’s work and read some of her writings at jillmueller.com or on instagram.